Sexual Harassment in Public Transit Spaces in Kenya

Sometime in 2018…

“Eh, siste!” (Hey sister) He calls out as he steps in my way, reaching out to grab my arm before I can dodge past. “Ingia hapa! Mbao tao!” (Get in here! 20 shillings to go to town!”). I can’t get loose as he shoves me roughly towards the half-filled van. I try to twist free but not before his other hand settles on my lower back to push me further towards the van. “Don’t touch me!” I try to protest, finally wresting free before he can shove me into the van. “Kwani unajidhani msupuu aje?” (How hot do you think you are?) He sneers as I back away quickly, only to stop when I get too close to the crush trying to enter a larger bus behind me. My arm is bruising from where he gripped me, and my hands clench on my bag. He is still looking at me, still sneering as I try to get around. I can only relax once his attention turns towards another potential passenger.

I wasn’t even trying to catch a bus, just walking past the terminal on my way to a government building in downtown Nairobi.

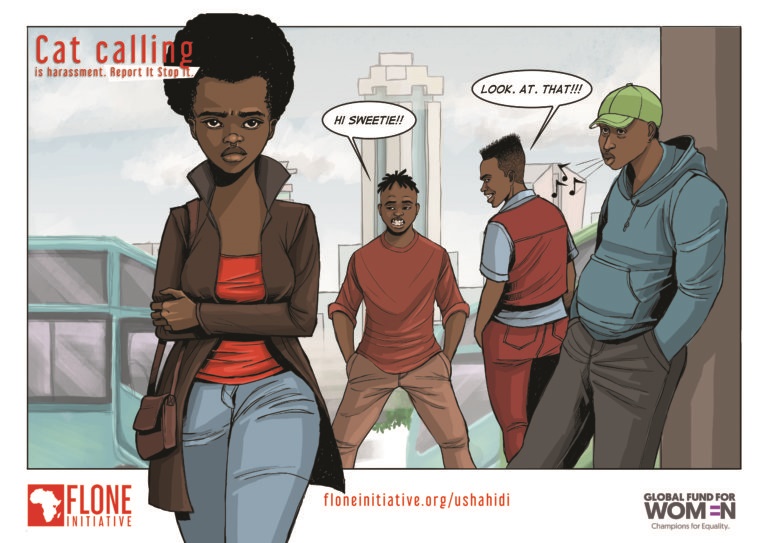

Abusive language and inappropriate physical contact are the norm for Nairobi’s matatu crews (minibus drivers and conductors) in coercing female passengers to board. The former increases if they refuse to board that particular vehicle. In Kenya’s public transportation system, the safety, security and dignity of female passengers is not a guarantee. Female passengers report having changed the way they dress and their travel routes to avoid victimization. This is a violation of human rights, essentially restricting women’s freedoms of choice and movement.

In November 2014, three videos of women being stripped and sexually assaulted at Nairobi bus terminals in Kenya went viral on social media, sparking international outrage and catalysing the #MyDressMyChoice campaign. Kenya already had a Sexual Offenses Act (2006) and an Anti-Stripping Law (2014) was soon passed but the reactionary response, criminalizing an act after the fact highlights an underlying issue with governance worldwide.

Administrative bodies do not respond to issues such as these until public attention is drawn by tragedy. Worse, cases of sexual violence in public spaces remain largely unreported due to the lack of full prosecution of perpetrators. The lack of protection for victims’ dignity and identities has been detrimental in encouraging reporting. The divided responses of the general public when extreme cases have been publicized is perhaps even more disheartening with moral judgement being the norm as opposed to questioning of the systemic issues that allowed for the case to occur.

Worldwide, the victims of sexual harassment are often blamed. The first assumption on reporting is often that they have done something to attract attention to themselves. In many patriarchal societies, the perpetrators are often seen as doing what men do while women are implicitly and explicitly criticized for causing a scene or complaining about what is seen as a part of regular life. In most cases, bystanders rarely intervene when they witness abuse even when research has shown that bystander reaction can significantly impact the prevalence of sexual harassment in public spaces.

Personal security therefore remains the primary concern of women transport users. They are subject to routine and systemic harassment by fellow commuters and service providers alike. Women face the risk of further harassment and even assault in transit spaces such as bus and rail terminals, a risk which increases with the evening hours. Underlying socio-cultural issues within a patriarchal system that objectifies women as possessions of their guardians and ignores their agency over their mobility only exacerbate this issue.

Women experiencing harassment may go as far as leaving work or school if public transit is their only option and they are tired or scared from the harassment they face. This significantly limits women’s lives and livelihood as alternative transit options may be less convenient, take longer or cost more than they can regularly afford. While a number of countries have adopted policies to address harassment in transit, many measures fail to address the core societal and behavioural issues that lie beneath this problem. Furthermore, basic interventions to enhance safety and security in public transit are considered too costly for many developing countries to implement.

This has significant impacts on individual, community and national development. Limiting the access to skill building, health and income generating activities for over half the world’s population can only be detrimental to the advancement of civilization. Existing interventions like gender-segregated carriages and buses can only provide short term solutions. A new normal that does not pander to outdated concepts of women’s agency over their mobility is needed alongside shorter term measures. If we are to achieve lasting change and sustainable development, then we must acknowledge and address the issue of sexual harassment in our public transit spaces.

By Nyaboke Omwega | Nairobi, Kenya | May-2020

Writer’s Note:

To learn a bit more about this issue, check out these links:

The #Mydressmychoice tag on Twitter: https://twitter.com/hashtag/mydressmychoice?lang=en

This article on sexual harassment on public transport in Kenya: https://floneinitiative.org/index.php/2019/08/07/report-it-stop-it-reporting-harassment-in-todays-matatu-climate/

This article on some research in Sri Lanka (still applies elsewhere in the world): https://www.oxfam.org/en/press-releases/sexual-harassment-public-transport-its-not-my-business-intervene-say-urban-commuters

This article on an ongoing UN Women Initiative called Safe Cities and Safe Public Spaces: https://www.unwomen.org/en/news/stories/2020/2/take-five-making-public-spaces-safe-for-women-and-girls

This report on said initiative: https://www.unwomen.org/en/digital-library/publications/2017/10/safe-cities-and-safe-public-spaces-global-results-report